In this exclusive interview with Kelly Carlin, Kelly reveals a more hidden, personal side of herself—the side that has emerged from her father, George Carlin’s, shadow. Jan invited Kelly to reveal some gems of wisdom from her experience with Buddhism and her graduate training in psychology. Listen to Kelly’s story about growing up with George (from the title of her memoir, A Carlin Home Companion: Growing Up with George), and hear her thoughts about becoming who you really are in the midst of a chaotic life. Find out what it takes, from Kelly’s perspective, to reach out and grasp those big dreams that scare you.

Full transcript of the interview

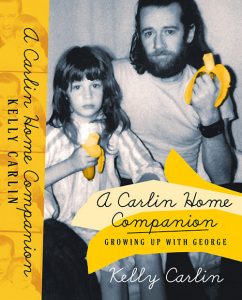

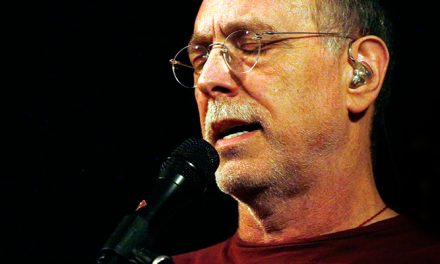

Jan Tucker: Welcome to Perfectinnerpeace.com. I’m Jan Tucker, publisher. Today I’ll be chatting with Kelly Carlin. She is the daughter and only offspring of George Carlin, who is our famous beloved comedian. He has been described as one of the most brilliant comedy minds the world has ever known, as well as hero of the counterculture, and the voice of a generation. I think by now he’s been the voice of more than one generation. George left this world in 2008. Kelly has been busy since then sharing her life story of growing up with George and her mother, Brenda. It’s a wonderful story of transformation and evolution of both Kelly and her family. She has captured this in her first book, which is memoir called, A Carlin Home Companion: Growing Up with George. Kelly’s story is one of finding herself through life’s turmoil. Because she’s been so successful at this, we can all learn a lot from it. I want you to know before we start that Kelly is an amazing woman in her own right. She has been an actor, producer, she’s an author and a master storyteller, an internet radio host with her own podcast and Sirius XM shows, and she’s a workshop leader. She leads workshops to help us grow beyond our own boundaries. She’s also, on top of all this, a trained therapist. She doesn’t practice therapy, but she uses it in her work. What may surprise you is that through all of this, Kelly is a practicing Buddhist, which is why I asked her to be with us today. With that, Kelly, welcome! I want to thank you for joining this interview with us. We’re all looking forward to what you have to share with us today.

Kelly Carlin: Well, thank you for having me, Jan. I appreciate this kind of forum, because lately at least, I have been coming with interviews through more comedy kind of venues, I don’t get to talk about my Buddhist practice and my training, and all my grad studies, and all that kind of stuff. So, these are my favorite conversations.

Jan: That’s great! Today we want to get to the real Kelly. Who you really are.

Kelly: Well, it’s all real, but you know, there are different slices of you that show up. So, I’m excited to be here with this.

Jan: Great, thank you. I thought we’d start off with some info on your dad. Most people know who your father was, but there are still some out there who don’t. And, I thought for them, as well as for people who know who he is, it would be great to hear from your own perspective, as his daughter, who was George Carlin?

Kelly: Well, my father!—He was a man who began his comedy career in his early 20s. He was a radio DJ first, but in his early 20s, he was in a comedy duo. Then, he became a solo stand-up. So, in 1963 when I was born, he was a starving artist and he worked with my mother, doing his best to get on TV on the old Jack Paar show and Ed Sullivan, and things like that. And he did—he got a lot! He was really good at what he did, so he got a lot of good breaks. So, he started his career in the 60s. And, in 2008, he was still at the top of his game and still cutting edge, and still crossing the line and making people laugh and think. And, in between those 50 years of being a standup, he helped revolutionize the art form. He was one of the pioneers who stood on the shoulders of people like Lenny Bruce and pushed the edge of language. One of his main topics was language. But, even within his career, he evolved two times in a major way to really transform who he was—on stage and what he talked about. So transformation and evolution was a thing in our family already just watching my dad do that.

Jan: I noticed that.

Kelly: Yeah. And, it’s part of his story. It’s part of the story that in my memoir, and in my solo show that I do of the same name and of the same material, that we really tapped into. It was the parallel transformations going on with my father artistically, and what was going on with the family and me personally. So, for people who don’t know him, just Google “George Carlin” and go to YouTube, and there’s a lot out there.

Jan: We’ve got it all.

Kelly: It’s all on there. And, it’s lots of language—dirty language and stuff like that. So, if you’re up with that, you’ll be happy. And, he’s very talented. He’s such a challenging comic, too. He does silly, silly stuff and then he does very, at times, strident, challenging things that really make us look at ourselves, especially Americans. We look at ourselves culturally and question what are we really doing. Are we just all lemmings following people, or are we thinking for ourselves? He was a man who changed people’s lives. And, I’m just so proud of what he did in his career. It was an amazing career. And he’s considered one of the top three all-time comedians in the 20th century, so it’s an honor. It was an honor to grow up in his shadow even though being in his shadow is difficult. And, I’m sure we’ll talk about that. But, it’s a real honor to know that he’s part of my DNA.

Jan: It would be an honor. He was just a fantastic person. Everybody that I know loved him.

Kelly: And/or loathed him.

Jan: That’s true. [laughing] I don’t know those people.

Kelly: Yes.

Jan: So, that’s what I want to get into next, what was it like growing up with him? This is just to set the stage. We don’t have to spend a lot of time on it. I’ve got a lot of other questions to go. But, what was going on with you?

Kelly: Well, you know, it was the 60s and the 70s when I was growing up. My father was one of the kings of the counterculture, and my mother was an alcoholic. She was even probably when I was very young, probably before I was born. So, it was really tough the first 12 years of my life until my mom got sober. And, those were years of the late 60s, early 70s when there was a lot of drugs and my parents were experimenting a lot. And, I was an only child. So, it was a very chaotic, dysfunctional at home. My dad was on the road a lot. I was stuck at home with mom. And so, I grew up very quickly. I had to be the grownup. And, if anyone else can relate to that, I’m sure you can—I bet many of you out there.

Jan: Yeah.

Kelly: Yeah. It’s challenging, because you don’t know how to take care of yourself. You don’t learn to ask the questions about what do I want or what do I need. So, that followed me into my teens and my 20s, where I, as a young woman, had no idea how to ask for what I wanted, or even think the question, really, and ended up in a crazy first marriage in my 20s with an older man, and more drugs and panic attack syndrome, and really difficult times. Until I turned 25 and I started to plot my way away from all of that and went back to school. I went to UCLA to get my bachelor’s. I was always a really, really good student, one of the smartest people in my class type of person. I love math and science. So, school was always something that gave me scaffolding. So, UCLA at 25 really gave me that scaffolding to find some pieces of myself. So by the time I was 29 I was able to leave my first husband and feel more like I found some semblance of myself at that point. There was still some healing to do. And, my parents were typical counterculture parents. They were laissez–faire—whatever you want, everything’s fine. My mom said yes to everything because she was afraid that I would rebel like she had and ran off with a crazy artist like my father.

Jan: God forbid!

Kelly: Yeah. And, my dad was a rebel, so he wasn’t gonna tell me what to do. So, in high school, we smoked pot together and stuff like that. So, it was kind of crazy…

Jan: Well, through all the turmoil though, I get from your book that there was still a lot of love in that family, you had a lot of respect. And, a lot of people that went through that aren’t able to do that. How could somebody get through that in as good a form as you did? Is it possible?

Kelly: I think I was really lucky in the sense that I always knew I was loved. I always knew I was loved even though there was all this chaos and it created some issues. I think if you don’t have a family of origin where you feel safe and you don’t feel loved, people find their new families and their new tribes. I know a lot of people, who I met through 12-step programs and things like that, did just that. No matter what we do, it does take a village. It takes a village to heal ourselves. It takes a village to go out, to have enough courage to go out in the world and do the work we’re gonna do. So, you have to find some people who you can relate to and who can relate to you. Like, in the Buddhist world, there’s our sanghas, our communities that we sit with. That can be a refuge. Twelve-step programs, fellow artists, all sorts of things. And, it takes a lot of courage and, I think, personal curiosity, to do this work and to heal yourself, willing to feel everything you need to feel. But, I was lucky. Once my mom got sober when I was 12, even though I was a teenager and, you know, you have issues with your mom anyway. But my parents were great people. They were both intelligent and they both were compassionate and funny, and had a great work ethic—both of them. So, it was easy for our family to stay connected. My parents had a little bit of baggage in their marriage for sure, but there was a joy. We had a joy with each other for sure.

Jan: That’s great. It really comes through. When did you find Buddhism? And, did that do a lot to help you along the way? And, how did you find it?

Kelly: Well, originally, I lived in Los Angeles, and we used to have this bookstore here which is no longer here, unfortunately, called the Bodhi Tree. The Bodhi Tree in the 80s was like Shirley MacLaine and all of that. It was like, “Oh, my God, we’re going to the Bodhi Tree.” My mom and I and my ex-husband and my best friend, we were all going to the Bodhi Tree and buy books. You know, there was all the astral projection stuff. It was the new age buffet! I’d always been fascinated by Zen Buddhism, but I was intimidated by it. It seemed—it felt like there was no magical thinking aloud in Zen Buddhism. And at the time, I needed my magical thinking. I needed my Edgar Cayce books and things like that. And, that’s fine. People are still into that kind of stuff. It’s all great. It’s just that I’ve felt like I moved beyond it. So, I remember buying a book called Chop Wood, Carry Water, something like that. And, it was just a book. And, it just sat on my bookshelf.

Jan: Wow. I can relate.

Kelly: Yes, we do. It’s like we know it’s gonna be good for us, but then we’re afraid. But, in 1997 my mother was diagnosed, in the early spring, with liver cancer. And, she had breast cancer about 14 years earlier, and been fine with it, and she had hep C. And, this was very serious liver cancer, nothing to do with the breast cancer. And, she died within five weeks.

Jan: Wow.

Kelly: It was very, very quick, as if she’d been hit by a truck. I mean, five weeks is nothing. And in our family, the way we practice communicating with each other, because we didn’t learn how to do that very well with our dysfunction, we were kind of all in denial about it. It was just too terrifying for all of us. And, I was 34 at the time and very, very close to my mother at this point in my life. And so, she died suddenly. And, that week after her death, there was this incredible sense of a numinous space that entered my life. There was just a lot of grief and shock. But there are also people who’ve been around us and had sudden shock or death. It feels like a veil is lifted in some way. So, I had this very big opening, this huge spiritual opening. There was a lot of love and joy inside of my body also right next to the grief. And, the thing that really struck me, and I think, strikes all of us when we lose our first parent, and especially when we’re in our 30s or younger than that even, or even on our 40s, is, “Wow, this death stuff is real!” And, you know what? There’s no promise in life. There’s no package deal or something. Tomorrow I could be hit by a bus.

Jan: Right.

Kelly: And so, I realized that I need to pursue the things that my heart and my soul really need to pursue now. And, I wanted to kind of come out of the closet as a spiritual being. Even though the new age stuff had happened in the 80s, for a while, I kind of put all that to bed. I had cassette of Thích Nhat Hạnh’s meditations. “Breathing in, I am like a flower, breathing out, I am fresh. Breathing in, I am like a mountain, breathing out, I am solid.” It was the only thing that I had ever meditated to—the only the only thing that had ever really helped me connect to that meditative state. And so, I got, I think it was a Shambhala Sun or a Tricycle Magazine. And, I looked in the back and oh, there was an advertisement to a Thích Nhat Hạnh retreat in Santa Barbara that fall.

Jan: Perfect.

Kelly: And so, I just signed up not knowing what I was getting into, what was gonna happen. And, I pictured like 50 people. It was at UCSB. It was gonna be this retreat I pictured, you know, a retreat like whatever the magical retreat ideal is. And, I get to UCSB and it’s the dorms, and it’s a gymnasium, and there’s 1200 people.

Jan: Oh, my gosh! Amazing!

Kelly: And you have to share a room…

Jan: You’re all squished in there together, right?

Kelly: Yes. And, you’re eating mindfully, and you’re sitting. I was completely freaked out! But, by day three I’m singing all the songs. I’m all in. I’m all in. And so, that was it. When I got home to Santa Monica, I found a sangha that was hooked up with his network, and started working with some local teachers at a sangha called Ordinary Dharma with Caitriona Reed and Michele Benzamin. And, it’s been 20 years.

Jan: So, that was literally your refuge.

Kelly: It really was. It really was. And, what was great about it, I was talking earlier about finding your tribe. One of the things when I went to the retreat the first time, I was like uh, these people who walk around and pretend like they’re: “I’m just the most spiritual thing in the world”—Yeah, not my cup of tea at all! So, when I found the sangha, I was really worried that it was gonna be a group of just holier-than-thou type of people. And, I was so happy to see that it was a bunch of misfits. It was a bunch of people who didn’t want to really be a part of anything and yet, here we were a part of those groups.

Jan: We’re kind of all misfits, aren’t we? It’s just that some of us haven’t found a home, yet.

Kelly: Yes, yes. And, part of the spiritual journey is when you first encounter these ideas, like I did in my 20s during the new age thing, is you think that you’re gonna find the secret key. You’re gonna find a book and you are gonna be like, “I’m going to find the secret.” Yeah, it’s not so much like that. And, you have to get to a point where you realize, oh, even if you hit an enlightened state kind of a thing, you’re not gonna stay there. You’re not gonna be—It’s not what you think it is.

Jan: It’s that Chop Wood and Carry Water thing—that first book that you picked up.

Kelly: It is; it is. It’s the, “Oh, I have to be human. And, I get to connect to these interesting states of consciousness and these interesting perspectives that that brings, but I don’t get a get-out-of-jail-free card,” which is what I used to think when I was first approaching my spirituality.

Jan: What does Buddhism think about the world? I know with Hinduism and with the path I’m on at Self-Realization Fellowship, we believe that the world is just an illusion. What does Buddhism believe about the world?

Kelly: Well, from what I’ve studied in Zen Buddhism, is that yes, it’s all an illusion and yet, we’re humans in a human body living on earth, and we are mortal. And, there are real consequences to your actions, and there are real consequences to emotions and all sorts of things. So it’s about being detached and fully responsible at the same time. It’s both these things. I mean, I’m not a scholar by any means, but from what I’ve learned, and I study mostly with a gentleman named Genpo Roshi now, who created this thing called Big Mind Process. And, he’s a bit controversial as many teachers who’ve had a great fall are. And, he had a great fall about five years ago. But, from what I have been studying with him and what I understand about the processes, I’ve been working on with him, is it’s all an illusion and it’s all real at the very same time—and it’s holding that. That’s the ultimate non-dual. It’s not black or white, it’s black and white.

Jan: And there’s also a reason for us to be here, right?

Kelly: Yeah.

Jan: What is that reason? That’s what a lot of people want to know. Why are we here?

Kelly: I’m not a person who’s into—not am I only a practicing Buddhist, but I’ve also studied a lot of Jungian and archetypal psychology. I have a Master’s in it. And so, I come from a real depth psychology perspective. I don’t think any doctrine or any dogma or any teachings can tell you what the meaning of life is or why we’re here. I think in Buddhism, the main thing is that it’s to alleviate suffering. That there is this idea that once you reach an enlightened state of consciousness and kind of felt some of those higher states, that you use that opening in order to be present and to bring compassion to the world to alleviate suffering for all beings, ultimately. And, that is a reason to be here. And, I also believe that each one of us has to find our personal meaning in our lives and figure out what it is that aligns our gifts with the world’s needs in some way, and to get in that juicy, joyful flow of that.

Jan: Kind of like our purpose?

Kelly: Yeah, kind of like our purpose. And yet, I like to sit with the tension of the opposites of it all. So, there’s this grand purpose with all of it, right, where we’re here to alleviate suffering or we have some sort of soul purpose or something like that. And then, there’s the reality that, you know, the way science looks at all of it, which I fully respect and own, which is that it’s all random and there’s absolutely no purpose and no meaning. And, when you sit with that reality, that’s a splash of cold water, and yet, it can lead you then, I think to that other thing which is really about, if there’s no purpose, and maybe our purpose is just to be kind to each other and alleviate suffering, what does that mean in this life, in my life, in this short one, precious life, as Mary Oliver says? You know, “What do you want to do with your one precious life.” Because tick, tock, tick, tock…

Jan: Right. And the older we get, the faster it goes.

Kelly: Oh, yes. I know that.

Jan: Well, I listened to your podcasts about the state of affairs with our political system right now. And, you include a lot of compassion in that. You did a nice meditation that led people through that. So, do you do that in your work?

Kelly: Yeah, I am definitely influenced by those beautiful, loving, kindness meditations that ask us to look past the exterior of people and look into their hearts and into their humanity, and into their own brokenness, and their own wounds. We were all two or three or four or five-year-old children at some point, and we are all heavily affected by our environment and our genetics. And so, as much as I love to rant and scream at the TV these days [laughing], I like to balance that with the idea of understanding that the people that piss us off the most are the people that if we can learn to sit with in our minds eye and see their humanity and see their brokenness in some way, we might have a chance on this planet on some level, you know. And, it’s not an easy practice. And, it’s not about excusing what they’re doing or diminishing it or giving them a pass, but it’s a different filter. It’s looking at them through your eyes in a different way. And, at the same time, writing your senator, and donating money, and getting on the streets and protesting if you need to, and voting. I mean, let’s remember that. Let’s vote, too. But, I think walking around in a state of panic and rage is really gonna only damage your own body in the end, and your own mind. And so, we have to figure out a way to deal with all of this in a way that keeps our hearts open.

Jan: Yeah, I think that’s the problem. We have two sides now, and we’re just at each other constantly. And, it’s not getting anywhere.

Kelly: Yeah. That’s why social media isn’t working for me anymore. It’s why I’ve taken the summer off from social media. It’s why I no longer engage in those kinds of conversations or confrontations on social media. Every once in a while I get hooked in and I’ll “Grrr!” Or, I have a great joke about something and I want to write something funny about it. And, that’s fine, too because that’s human. That’s who I am, but it’s not where I live. I can’t live there 24/7. And, yeah, it can feel really—If that’s all you’re doing all day—watching that stuff—the world will get very dark very quickly.

Jan: Yeah, it does.

Kelly: You have to take it in doses, in very small doses.

Jan: I would agree with that. Let’s switch gears for a minute and do something fun. Do you think that we choose our parents?

Kelly: I don’t know. I do and I don’t. I used to really be into that and really think about that, like, oh, we choose our parents. And then, it’s really a beautiful exercise to do, to stand in that perspective, and to see how, what is it that I came here to learn, and what did I come here to teach my parents, also. And, it can really help you put your family of origin story in a different light because the whole teaching and receiving thing—it makes it a bigger conversation than victim-perpetrator. It just does. So, I find the perspective to be really, really interesting. My dad and I used to talk about this after death thing, because you know, even though I’ve had some encounters with my dead parents, I can’t tell you that I had encounters with my dead parents. I’ve had some sort of encounter. Is it imaginal? Is it them? I don’t know. Have I done some interesting past life regressions in my past? Absolutely! Fascinating. Do we have any proof that there’s life after death? Not really. I mean, it would be front page news if we had real scientific proof of it. So, I used to say to my dad, “Look, here’s my theory about this. If when I die if there’s like a white light and you guys come and greet me and we go and hang out and we’re in our astral bodies or whatever, we’ll be like, ‘Oh, that’s great! Oh my, God. It really is like this. This is really cool.’” “And if it isn’t—I won’t know!” [laughing]

Jan: True, very true.

Kelly: “Either way, I’m gonna be okay.”

Jan: Fair enough.

Kelly: But, I do like the exercise of the perspective. And, I can be an absolute skeptic atheist and sit in that position, at the very same time, talk about my soul being an acorn and it unfolding into the oak tree that it is, because of some…What is it? Telos, T-E-L-O-S, that Jean Houston and James Hillman talk about, this kind of blueprint for our life that unfolds, because it really does feel like that for me a lot of the times when I look at my life. I feel like, yeah, there is a plan. And, I can feel my way into situations where I know there are things I need to work on in my life, and so I find myself attracted to confronting those and stepping up and revealing myself. That’s really what the last eight years of my life has very much felt like, but really like the last 20. I think you do get to have your cake and eat it, too, in a sense. You really play with both perspectives and have a rich, meaningful life.

Jan: I know that you do things spontaneously quite a lot. And, it sounds like, in reading your book, when you get into a situation where you’re in trouble, you’re fearing something, you just kind of sit back and say, ”Okay, what’s next? What do I do next?” And, I know so many people in this life who can’t do that. They’re afraid. They do wanna just follow a pattern. What do you recommend? What’s it like when you just go with the flow?

Kelly: Yeah. I mean, you know, I had to learn how to do that, first of all.

Jan: Okay.

Kelly: We’re not trained to go with the flow. Unless that’s kind of your strategy. For some people, that’s their strategy of survival, to go with the flow.

Jan: True.

Kelly: So, a little something different would be better for them. Until my late 20s, my mid-30s, really until my mom died, I was a person who felt very trapped. I felt trapped by my anxiety and felt trapped by a lot of self-doubt and confusion and self-sabotaging in my career a lot. I think it was my mother’s death that really showed me, “Oh, no one’s gonna fix anything for me. There’s no magic wand. No one’s gonna rescue me. No one’s gonna hand me the life I think I deserve. And so, I’m gonna have to step up to the plate and tackle some things that are going on inside of me.” And, I wasn’t always able to tackle them head on. I mean, my relationship with my father was a very delicate dance for me. My ability to feel fully expressed in front of him, and to go out in the world and do my art and do my work, felt very stymied by his presence and his big, powerful shadow and success. And, it took his death for me to have permission to go out in the world to do that. It took therapy. It took the ability to have a practice like a sitting practice or some sort of spiritual practice, where I was learning to watch my mind and my thoughts and to see how full of shit they were most of the time. It takes surrounding yourself with people who are healthy and believe in you and are there to pull you down. It just takes a lot of courage to do these things. You have to be willing to face your fears and get out of your comfort zone.

Jan: How do you do that when somebody is in a situation where they’re just frightened about something? You know, they’re trying to move forward and they’re stuck or something just happened. How do you deal with that kind of a situation?

Kelly: So, something has to be bigger than your fear in that moment. You have to want something more than your fear is going to keep you down. And so, part of it is getting to know yourself and getting to tap into, what is it that you really love. What are those inner—what are those things? What are those big dreams that when you dream them scare the hell out of you, but at the same time give you butterflies? Like, “Oh, I really want that.” For me, I remember seeing Spalding Gray, who is this great storyteller, and Karen Finley, who is a big performance artist in the 80s, seeing them both and thinking I wanna do that someday. I had no idea how to do that. It terrified me. I had stage fright, the whole thing. I always held that in my head, in my mind that, I need to tell my story to the world. For whatever reason, I need to tell my story. That desire, that urge, that craving to do that thing, even though you have all these obstacles and fears in front of you, that’s pulling you forward toward something. So, you need a vision for your life in some way, so that when the fear comes up, you remind yourself, “What am I doing this for?” And, you also need support. You can’t do this by yourself. I couldn’t do it by myself. I needed people around me who believed in me, who encouraged me, who supported me, sometimes with the actual work I was doing in the world, partnering with me. And so, you know, it helps to have a therapist or even a life coach or a writing group, or any kind of a group that you’re in where you can get some sort of support, a mastermind group—finding four other friends who also have big dreams who wanna do something that will scare the hell out of them. Get together and support each other.

Jan: People with like minds are always good to be around.

Kelly: Yes, people with like minds. And then also, reading. I read a lot of biographies of artists and stuff, and see that there’s a lot of failure involved. You have to be willing to fail. And for many, many years, I was not willing to fail. Perfectionism was the biggest killer—creativity killer in my life. Because I looked at my father who was perfect in so many people’s eyes. And to me, he was perfect. He seemed like he had this like flowing natural path to this great god of comedy. And of course, he had so many doubts and fears and things along the way, but he didn’t share them with me. I was his kid, you know. But, willing to learn along the way, learning to fail, that has taught me more in the last 10 years of my life than anything. That has been the secret potion. It’s knowing that you’re not gonna die. You’re not gonna disappear. The walls are not gonna fall in on you, and the earth is not gonna open up. Those are all of our fears about these things that if we fail. And the voices in your head that tell you that you are worthless and stupid and all of that, are actually lying to you. Those are the voices of the status quo. And the status quo—its job is to maintain the status quo.

Jan: I love it. I love that. That’s very helpful.

Kelly: Yeah. And so—know that’s its job. And yet, that’s just one voice in your head. Because, there are other voices that are the champion of you, and the visionary, and the little kid who wants to play, and all that kind of stuff. So, you can put the status quo over to the side and say, “Thank you, that’s very interesting, status quo. I get that—you’re terrified.” And, this is the ego voice. This is the voice of the ego. “That’s very nice of you. I get that your job is to keep me safe and protect me. And, you know what? I’m 54 years old now. You’ve been doing a great job. I’m still here. Look at that! Thank you! But, with this particular little project, or this idea or this thing I’m gonna do, I’m just gonna put you over here. And, you’re gonna be in a box, and I can’t hear you!”

Jan: That’s awesome, very awesome.

Kelly: Yeah! yeah.

Jan: You know, from the outside looking in, it occurred to me that your dad spent a lot of time explaining why we have a crazy society. It’s just a bunch of just idiots, basically. And then, has it ever occurred to you that he kind of set it up for you, so that you could come and tell us how to get through that?

Kelly: [Laughing] Yeah, you know, I’ve had a couple of people in my life who have set the stage in that way for me. They’ve said, “We’re all here to stand on our parents’ shoulders. We’re all here to stand on the generation before us and the work they’ve done.” And, yeah, I believe I’m here to bring something a little different. My dad—his great gift was in looking out at the world and seeing what was wrong with it. And, he was very articulate and observant about that. And, he also did observational comedy and shared what was going on in between us, the kind of the things that we notice in our days and the “stuff routine” and all that kind of stuff. My whole focus has always been this direction—it’s inward. And I needed to do that in order to heal myself and to find myself and figure out who I am. So, I’ve had a lot of time and practice looking inward. And now, I’m shifting also in And now, I’m shifting also in this way—what does that mean then for who we are in the world together, how do we treat each other. So, it’s beyond observations of things. It’s about actual relationship and understanding. I think Buddhism more than anything has taught me about the interdependence of each and every one of us on this planet. You can stand on a stage and complain about things, but ultimately, that’s not going to move anything forward. It may wake people up. And, my dad did wake a lot of people up even though he was interested in making people laugh. He would always say, “I’m not interested in waking people up.” And yet—hello!

Jan: Right.

Kelly: So, I’m interested in waking people up and giving people a couple of things that they can do so that they can actually move out into the world and do their work in the world, because, that’s been my challenge for so many decades. And, it’s been really cool the last six years especially, to have started to move out in the world and to be able to share my mind and my heart and my perspective, and bring the Carlin perspective to the inner life and spiritual work, and a different way of observing the world. I think I’m a keen observer like my father, but at the same time I’m interested in the species making it, whereas my dad was a little…[laughing]

Jan: He thought we were hopeless.

Kelly: He had given up on us.

Jan: Yeah, it’s hopeless.

Kelly: And, I get it. I mean, the last year—more and more I think—is he right? How do you admit my father’s right? It’s too much.

Jan: There’s always hope, Kelly. There’s always hope.

Kelly: Yes, there is. There is. And there’s something very bracing and freeing about not having hope, too. There’s a Zen perspective of no hope that can lead you to a deeper sense of hope. There’s kind of a false hope, which is kind of the fairytale unicorn rainbow one. That’s not gonna work. And then, there’s no hope which is kind of a letting go of like, “Wow, it’s all an illusion and it’s all bullshit, and we’re all doomed, okay.” And then, what comes from that? What emerges from that? And, I love that. That’s my favorite place to be with, working with individuals or groups looking at the world. It’s like there’s always the first perspective, which is kind of the pedestrian one. And then, there’s the rejection of the mainstream. And, there’s the kind of the screw you, “I’m gonna reject everything” and be in kind of the dark night of the soul. And then, what comes from that? What comes from the journey from the underworld? What comes when you really sit with your own death, or the reality that this planet is dying, and that we’re killing it and we might not make it? What comes from that when you really are able to sit with the deepest darkest thoughts and realities? I think there’s a bracing hope that can emerge that’s more mature, but it takes a lot of personal responsibility to sit with.

Jan: And, we’re probably not quite there yet, right?

Kelly: Yeah, there are percentages of people who are. I saw the trailer for Al Gore’s next movie. He’s there. He’s there. He sees it. He sees the reality. And, he sees some hope because of it.

Jan: And, he’s sure it’s gonna happen, too. I’ve seen him speak.

Kelly: He is, man. And, this new documentary is very bracing. The trailer is very bracing. And yet, it makes you want to stand up and cheer because someone’s finally speaking some truth. That’s what it is, we know bullshit when we hear it. And, we know truth when we hear it. That’s why my father was successful because we heard the truth in what we said. What do we do with that truth? How do we stand up as individuals? In our own personal lives when we have to face the truth about ourselves, and as a species, and as a country, and as a culture, like, all those different things, what do we do then?

Jan: What kind of advice would you give people? What’s Kelly’s main thing? Do you have a main thing that you’d like to share?

Kelly: I think my main thing really is—and it really is a culmination of how I was raised and the life experience I’ve had and everything, which is that you have to be able to step away from the crowd. And, that is the culture. That is the crowd in your head that’s been brought to you by your education and your family of origin and your culture, to really connect to that still small voice inside of you. And, it’s there in all us. And, I know a lot of people always say, “Yeah, but there are so many voices in my head.” But, there is one that resonates with you. And, that resonance is found when you are connected to things that bring you joy or beauty or that truth. And, I want everyone to be able to have that in their life, to be able to access that. And, you access it just by walking outside and watching a sunset, and taking the time to do that. There’s something about being in your 50s when you just don’t give a shit anymore. I just find myself, I don’t care. I’m at a restaurant and I will just be like, “Oh, my God. Look at the sunset.” And, I’ll be like, the person next to me, “Look at the sunset. Get off your phone and look at the sunset,” you know? So, it’s not really advice, it’s really what I hope for people. It’s to not buy in to what everyone’s selling—really.

Jan: That’s something that would make a better world for sure.

Kelly: Yeah.

Jan: That’s a great piece of advice. So, how about, can you tell us what you’re up to next? I think you’re maybe getting ready to write another book.

Kelly: Yeah. I am in the middle of 10 live webinars that I’ve been doing over the summer. It’s called Unplugged with Kelly Carlin. And, I just invited people to come along and unplug, like literally unplug from your… well, the irony is, it’s online. Okay, so, it’s not completely unplugged. But, I invite people to get off of social media or whatever the thing is they need to do in order to connect back to themselves. So, I offer a sitting meditation and then, I offer a talk about something, and I do some coaching and Q&A. I’ve been bringing mindfulness to people that way, which is really great. The first webinar, we ate a grape in five bites. And, people have never done that and their mind is blown. “What?!”

Jan: Amazing.

Kelly: So, I get great joy in doing that. So, I’m doing that. I’ll probably do another one in the fall because I’m just having a lot of fun with it. And yes, I’m working on a second book idea. And, it’s around the father-daughter relationship. It’s about how women need to let go of and reframe and investigate and rework their relationship with their—maybe not their personal father—but definitely their inner father. Because as women, in order for us to do our work out in the world, we need to have a sense of permission and a sense that our work is worthwhile. And, generally speaking—I’m not speaking for everyone—but generally speaking, we get those messages from our fathers, because that’s who traditionally has gone out in the world and done the work. Women are doing that now, but just as in the masculine. We’re talking depth psychology, Jungian archetypal stuff. The masculine is the one going out, the feminine is the one that’s receiving. So, when we’re going to go out in the world and do our work, we need to have a healthy relationship with our fathers and our inner fathers and our masculine. So, I’m writing about the last 8 years of my life after my father’s death and my real wrestling with this in an interior way, so I could go out and start doing my work in the world, including my solo show in the book that you held up earlier. So, it’s around this concept of daughterhood. And, I’m very excited about it. It’s cool. It’s cool because I get to talk about all the juicy stuff that you and I are talking about, that I get to tell all my stories about my adventures and getting on stage and doing all these things, and getting to hang out with cool comedians and all of that, while at the same time wrestling with my self-doubt and my identity and my ego, man. My ego shouts out. It was like, “Oh, I’m in the spotlight. Oh, I like this.” And, watching that as a Buddhist, it was like, oh my god! And, I’m gonna give a shout out to my friend Garry Shandling, who is no longer with us. He was a practicing Buddhist, too. And, he was one of my teachers during that time. He really helped me about taking the spotlight and doing it in a way that is unattached to the outcome.

Jan: That’s great.

Kelly: Yeah. So, that’s what I’m up to right now.

Jan: That’s something to look forward to. And, I just want to share, too before we move on. In your first book, you have a wonderful letter. It’s an email that you sent to your dad and he answered you. I think we just need to leave that as a mystery for everybody, but it’s just a tear-jerker to read that. It was so touching.

Kelly: It still makes me cry to this day when I read it.

Jan: Totally awesome.

Kelly: Yeah. Thank you, Jan.

Jan: You’re welcome. So, what else? You were about to say something else?

Kelly: Nothing. I might start up my podcast again to kind of be in support of these webinars I’m doing, because I’m really enjoying the webinars. And, really, the last year has been about walking away from my dad and walking away from being “the daughter of” in the way I was in the past where I was always talking about him in the book. I mean, it was all part of it. It was all beautiful. It was all something I had to walk through the fire of to know that I’d be done with it someday. And, I am done with it now. So, now when I talk about him, it’s with a real sense of “Yeah, that’s him over there and yet, this is me here and he doesn’t define me anymore.” But, it’s been an interesting road to watch my ego work with that and really having to sit with it. Literally, sit with meditation and to just sit through the emotions of it. It’s been challenging, but I highly recommend it [laughing].

Jan: I’ll bet. And, you know, it’s something to really look forward to for us, too. I’m very glad you’re out from under the shadow. I’m very glad to know you. I think you’re a wonderful, amazing—just a really good role model for women.

Kelly: I appreciate that. That means a lot to me. I also feel like a human that knows has no idea what the hell I’m doing [laughing still].

Jan: And, we’ll celebrate that part, too!

Kelly: Yes. It never goes away.

Jan: Right. Well, thank you so much for spending this time with us, Kelly. And, I hope you’ll come back one day and tell us the saga—the continuing saga of Kelly Carlin.

Kelly: I would love that, Jan. And, thank you for doing this. And, thank you for offering this to people. This is a great service you’re doing.

Jan: Awesome.